Bearded seals inhabit circumpolar Arctic and sub-Arctic waters that are relatively shallow (primarily less than about 1,600 feet deep) and seasonally ice-covered. In U.S. waters, they are found off the coast of Alaska. Learn more about the bearded seal.

Bearded seal in Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Credit: John Jansen, NOAA Fisheries

Bearded seal in Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Credit: John Jansen, NOAA Fisheries

Bearded seal in Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Credit: John Jansen, NOAA Fisheries

Bearded seal in Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Credit: John Jansen, NOAA Fisheries

The bearded seal gets its name from the long white whiskers on its face. These whiskers are very sensitive and are used to find food on the ocean bottom.

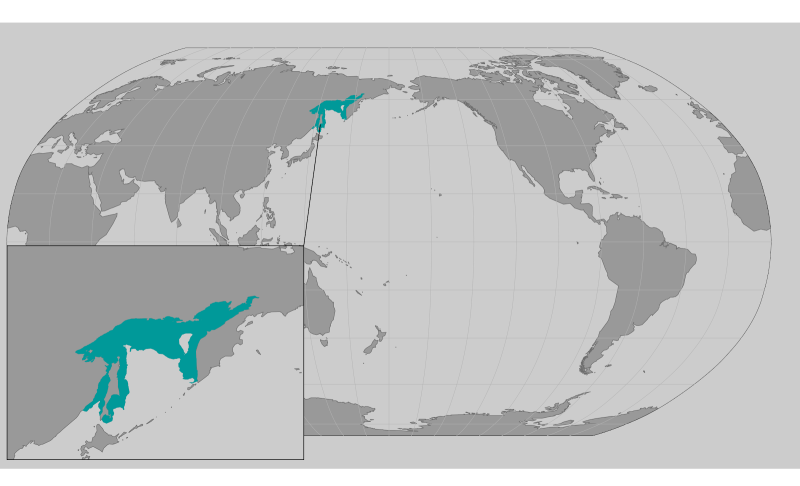

Bearded seals inhabit circumpolar Arctic and sub-Arctic waters that are relatively shallow (primarily less than about 1,600 feet deep) and seasonally ice-covered. In U.S. waters, they are found off the coast of Alaska over the continental shelf in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas. Because bearded seals are closely associated with sea ice, particularly pack ice, their seasonal distribution and movements are linked to seasonal changes in ice conditions. To remain associated with their preferred ice habitat, bearded seals generally move north in late spring and summer as the ice melts and retreats and then south in the fall as sea ice forms. As such, they are sensitive to changes in the environment that affect the annual timing and extent of sea ice formation and breakup.

Bearded seals, like all marine mammals, are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. There are two currently recognized subspecies of the bearded seal:

The geographic distributions of these subspecies are not separated by conspicuous gaps. The Okhotsk and Beringia distinct population segments (DPSs) of the Pacific sector are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Because of their listed status, these distinct population segments are also designated as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

There is no accurate population count at this time, but it is estimated that there are probably over 500,000 bearded seals worldwide.

The Beringia stock is the only stock of bearded seals in U.S. waters.

Although subsistence harvest of bearded seals occurs in some parts of the species’ range, there is little or no evidence that these harvests currently have or are likely to pose a significant threat. While the United States does not allow commercial harvest of marine mammals, such harvests are permitted in some other portions of the species’ range; however, there is currently no significant commercial harvest of bearded seals and significant harvests seem unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Bearded seals are the largest species of Arctic seal. They grow to lengths of about 7 to 8 feet and range from about 575 to 800 pounds. In some regions, females appear to be slightly larger than males. Bearded seals have generally unpatterned gray to brown coats, large bodies, and small square fore flippers. They have a short snout with thick, long white whiskers, which gives this species its "beard."

Bearded seals primarily feed on or near the sea bottom on a variety of invertebrates (e.g., shrimps, crabs, clams, and whelks) and some fish (e.g., cod and sculpin). While foraging, they typically dive to depths of less than 325 feet. They do not like deep water and prefer to forage in waters less than 650 feet deep where they can reach the ocean floor. Still, adult bearded seals have been known to dive to depths greater than 1,600 feet.

Bearded seals tend to prefer sea ice with natural openings, though they can make breathing holes in thin ice using their heads and/or claws. Sea ice provides the bearded seal and its young some protection from predators, such as polar bears, during whelping and nursing. Sea ice also provides bearded seals a haul-out platform for molting and resting. Bearded seals are solitary creatures and can be seen resting on ice floes with their heads facing downward into the water. This allows them to quickly escape into the sea if pursued by a predator. Bearded seals also have been seen sleeping vertically in open water with their heads on the water surface.

Bearded seals are extremely vocal, and males use elaborate songs to advertise breeding condition or establish aquatic territories. These vocalizations, which are individually distinct, predominantly consist of several variations of trills, moans, and groans. Some trills can be heard for up to 12 miles and can last as long as 3 minutes.

Bearded seals are circumpolar in their distribution, extending from the Arctic Ocean (85° north) south to Hokkaido (45° north) in the western Pacific. They generally inhabit areas of relatively shallow water (primarily less than 650 feet deep) that are at least seasonally ice-covered. Typically, these seals occupy ice habitat that is broken and drifting with natural areas of open water (e.g., leads, fractures, and polynyas), which they use for breathing and accessing water for foraging.

In U.S. waters off the coast of Alaska, bearded seals are found over the continental shelf in the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas. The shallow shelf of the Bering and Chukchi Seas provides the largest continuous area of habitat for bearded seals. In late winter and early spring, bearded seals are widely but not uniformly distributed in the broken, drifting pack ice, where they tend to avoid the coasts and areas of fast ice. To remain associated with their preferred ice habitat, most adult seals in the Bering Sea are thought to move north through the Bering Strait in late spring and summer as the ice melts and retreats. They then spend the summer and early fall at the edge of the Chukchi and Beaufort Sea pack ice and at the fragmented edge of multi-year ice. Some bearded seals—mostly juveniles—remain near the coasts of the Bering and Chukchi Seas during summer and early fall, where they are often found in bays, estuaries, and river mouths. As the ice forms again in the fall and winter, most bearded seals are thought to move south with the advancing ice edge.

approximate representation of the bearded seal" width="800" height="405" />

approximate representation of the bearded seal" width="800" height="405" />  approximate representation of the Okhotsk DPS of bearded seal" width="800" height="486" />

approximate representation of the Okhotsk DPS of bearded seal" width="800" height="486" />

approximate representation of the Beringia DPS of bearded seal" width="800" height="445" />

approximate representation of the Beringia DPS of bearded seal" width="800" height="445" />

In general, bearded seal females reach sexual maturity at around 5 to 6 years and males at 6 to 7 years. Females give birth to a single pup while hauled out on annual pack ice, usually between mid-March and May. Pups are nursed on the ice, and by the time they are a few days old, they spend half their time in the water. Pups transition to diving and foraging while still under maternal care during a lactation period of about 24 days. Within a week of birth, pups are capable of diving to a depth of 200 feet.

Males exhibit breeding behaviors up to several weeks before females arrive at locations to give birth. Mating takes place soon after females wean their pups.

Bearded seals rely on the availability of suitable sea ice over relatively shallow waters for use as a haul-out platform for giving birth, nursing pups, molting, and resting. As such, ongoing and anticipated reductions in the extent and timing of ice cover stemming from climate change (warming) pose a significant threat to this species.

The continuing decline in summer sea ice in recent years has renewed interest in using the Arctic Ocean as a potential waterway for coastal, regional, and trans-Arctic marine operations, which pose varying levels of threat to bearded seals depending on the type and intensity of the shipping activity and its degree of spatial and temporal overlap with the seals. Offshore oil and gas exploration and development could also potentially impact bearded seals. The most significant risk posed by these activities is the accidental or illegal discharge of oil or other toxic substances because of their immediate and potentially long-term effects. Noise and physical disturbance of habitat associated with such activities could also directly affect bearded seals.

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 05/10/2024